We know language. Whether we’re discussing the etymology of our agency name or toying around with different ways to use “literally” in a sentence, we enjoy putting language to use and revealing both its secrets and idiosyncrasies. That knowledge and enjoyment comes from a deep appreciation for and understanding of the English language and its history. Two words, “legal” and “loyal,” share a surprising history – one that may shed particular insight into how we understand the concept of trust.

Use Your Imagination

When people think of the word “legal,” they often imagine things like cold Ionic pillars (at the precipice of vast stone staircases), dark oak interiors, mountains of paperwork, gavels (as well as the harsh cracking sound they make), and perhaps the black robes worn by the judiciary. The most human association many people have with the word “legal” may be sketch artist renderings of a criminals on trial in closed-off courtrooms. There’s even a word in English that was created just to describe how aloof and incomprehensible the language of lawyers, contracts, and politics is: “legalese.” We describe documents, systems, and inanimate objects as “legal,” and the word’s connotations are not often positive.

On the opposite side of the linguistic spectrum is a word only 2 letters divorced from “legal.” “Loyal” is a word almost exclusively applied to people, and it embodies much of what we desire in others and strive for in ourselves. The word “loyal” conjures images of chivalrous knights on horseback, of best friends (or even family members) who would do anything for one another, and of soldiers in the line of duty fighting to protect the home they’ve left behind. “Loyal” is a powerfully human word, and while it sometimes bestows honor onto other things – the loyal family dog, perhaps – we don’t speak of “loyal” paperwork or the complex “loyal” system in the United States.

“Legal” and “Loyal”: Twins?

With words that mean such different things, it may come as a surprise that these words are actually etymological twins. In linguistics, we call them doublets: separate words that have arrived into a language from the same place. In the case of “legal” and “loyal,” both words came from the Latin root “legalis.”

A History of the Word “Legal.”

Seeing how “legalis” became adopted as the word “legal” in English doesn’t exactly require a degree in linguistics – the words look remarkably similar. The word “legalis” is a Latin derivative of the word “lex,” which meant “law.” Interestingly enough, the English word “law” – although seemingly similar to the Latin word “lex” – actually came from the Anglo-Saxon word “lagu,” which came from Old Norse rather than from Latin and meant “something laid down or fixed.” This is fitting given that some of the earliest recorded laws – like the Code of Hammurabi – were chiseled into large stones (called stele) and set up in prominent locations for everyone to read.

Thus, the words “law” and “legal” in English come from different linguistic roots. And while the word “law” (and its earlier form “lagu”) was used in written English since the 11th century (and probably much earlier), the earliest uses of “legal” in written English are from the 15th and 16th centuries. This suggests that the word “legal” came into the language during the Middle English period in one of two ways.

The first and most likely is through French. Many people don’t realize it, but French was – ironically – the official language of the courts and government of England from 1066 to approximately 1417 when Henry V began promoting the use of English in the government; before that, the English language had only been officially recognized in the courts as a result of the Pleading in English Act of 1362 after the English populace complained about not being able to understand what was being said for or against them in the courts of law (since French was the language in which trials were conducted). This also illustrates the second possibility for how “legal” came to be used so widely in English: it could have come directly from Latin since all court records were documented in Latin, and most lawyers and government officials could read and write in that language as well as French.

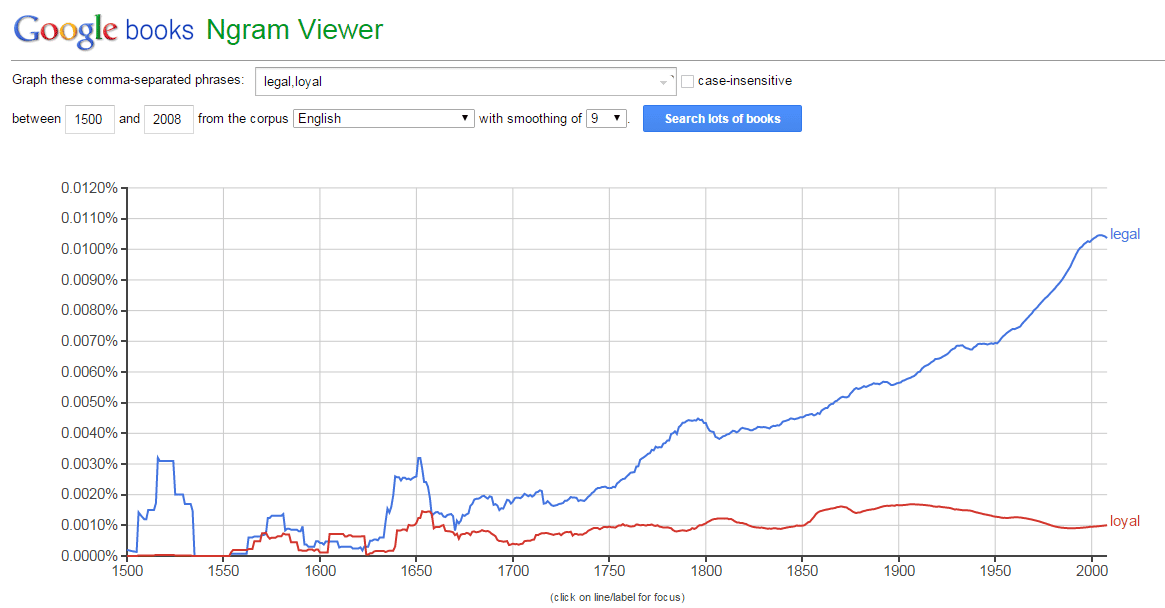

Regardless of how it entered the vernacular, it was in relatively wide circulation among English speakers by the 17th century and has been growing in popularity ever since. In fact, it is the 964th most frequently used word among all the books included in Project Gutenberg and is preceded on that list by commonly-used words like “north,” “expect,” and “twelve” and followed by words like “darkness,” “advantage,” and “taste.”

A History of the Word “Loyal.”

Although it may not look like it, the word “loyal” is also derived from the Latin word “legalis.” In order to understand how, you have to know a little bit about Middle English pronunciation. First, the word “legalis” was adopted into Old French. This was centuries before the printing press was invented and long before any kind of institutionalized language standardization was taking place; thus, in Old French, the word “legalis” was adopted in various forms like “leal,” “leial,” and “loial.” This was a fairly common occurrence in languages before the advent of the printing press; in English, for example, the words “church,” “chirche,” “cherch,” “churche,” “cherche,” “kirk,” and “kirke” all meant the same thing in different parts of England.

Next, the French word “leal” was adopted into English around the 13th century, and it was likely pronounced as “lee-all” (rather than rhyming with “feel,” as it is pronounced today). Early on, the adjective “leal” in English meant something like “fulfills legal obligations.” Within the feudal system, this often meant that someone faithfully performed military service as part of what was effectively a land contract (but that’s a history lesson for another day). Over time as the legal structure of the feudal system broke down, performing military service voluntarily truly became an indication of loyalty rather than simple obligation. Thus, the word “leal” came to mean “loyal, faithful, honest, true.”

About 250-300 years after “leal” became adopted in English, the word “loyal” – also from French and originally from the Latin “legalis” – begins to replace it and become much more popular. For example, in Shakespeare’s works, the word “leal” does not appear at all, but “loyal” and its derivations like “loyalty” appear 76 times.

Why did “loyal” become dominant and “leal” pass into obscurity even though it was in the English language for almost 300 years before “loyal”? This could be the result of several factors. One factor could be the geographical origin of the words. “Leal” may have begun its journey into English in a less-traveled region like Scotland, which is the only place it remains in wide circulation today; like any transient meme, the word may have come in contact with just enough people to subsist but not enough to spread. In contrast, “loyal” may have circulated among a much larger population (or a population of more influential people – like Shakespeare) and become more popular.

An alternate explanation could be the conflation of the two words at exactly the same time that the spelling and usage of the English language were becoming standardized via the printing press and educational institutions. “Lee-all” and “loy-all” may have been pronounced in a remarkably similar way in various parts of England. As works got published and the language became taught, “leal” may have just been “corrected” to “loyal,” thus cementing the word’s dominance in the language. Or, it could have been a combination of both factors.

Loyalty, the Legal System, and Trust.

Among all the books in Project Gutenberg, “loyal” is ranked 3,348th in the list of most commonly used words in English, and although its use in literature has been steady over the past few centuries, it is not nearly as pervasive as the word “legal.”

The proliferation of the word “legal,” particularly in the 20th century, may very well be a result of the concurrent proliferation of legal action – particularly in the United States. From Brown v. Board and Gideon v. Wainwright to Citizens United and Obergefell v. Hodges, the last 100 years have seen some of the most significant legal decisions in American history. It’s no wonder, then, that legal matters would increasingly be at the forefront of English language discourse.

On the other hand, the relative rarity of the word “loyal” perhaps speaks to its value in our society. We admire those who remain loyal to their convictions, we seek out friends who remain loyal to us, and even among those who are more material-minded, there’s nothing more sought-after than customer loyalty.

But loyalty needs to be earned, and this is where “loyal” and “legal” share a deeper relationship. Loyalty is, in many respects, an outcome of trust. We enter relationships of all kinds with basic expectations – whether they are assumed or they are laid out in a contract or warranty. When a company produces something of quality that meets or exceeds our expectations, we’re more likely to remain loyal to that company the next time we make a purchase. We trust them. If a company breaks our trust by not meeting those expectations – or even by causing harm to us – we seek recourse for that breach, and the legal system is founded upon righting wrongs of all kinds. “Loyal” and “legal,” then, are essentially opposite outcomes – when trust is built, loyalty results; when trust is broken, the legal system provides refuge.

As a legal marketing agency, we know what your potential clients expect from law firms – both online and in person. First and foremost, they expect you to deliver quality. From useful, informative news and content to personalized, relevant e-mails or even high-quality videos, we can help you gain the trust and loyalty of potential clients so your legal practice can thrive. Call 888-222-1512 today to learn more about how we can work with you to grow your firm.