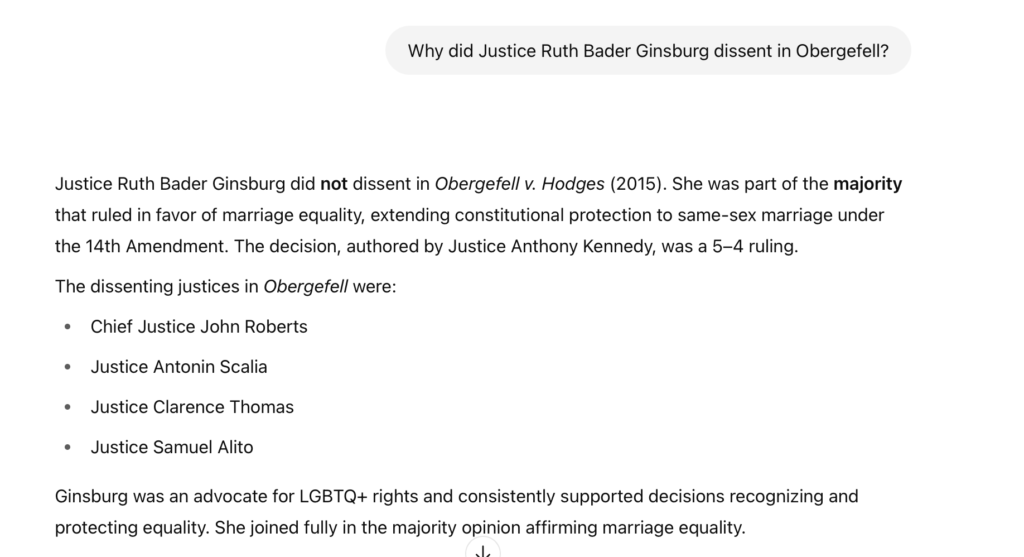

In the early days of AI (way back in 2023), SCOTUSblog’s editor asked ChatGPT a series of questions about the Supreme Court’s history and jurisprudence. The generative AI tool repeatedly asserted that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented in Oberfegell v. Hodges, the landmark case that legalized same-sex marriage. Oof.

I asked a similar question to ChatGPT’s 4.5 model. Thankfully, it gave me the correct answer.

Referencing RBG and AI isn’t clickbait. I’m referencing this story because it highlights a very real, and increasingly dangerous reality.

AI sucks at legal analysis. And lawyers are relying on it at their peril.\

Confidently wrong: The hallucination problem

If you’ve practiced law in the last two decades, you’ve already seen technology reshape the profession. Online research replaced rows of reporters. E-discovery tools took the tedium out of document review. Automation crept into intake, billing, and scheduling. (And let’s be honest, none of us miss flipping through Shepards in a law library.)

So when generative AI showed up, seemingly capable of summarizing case law, drafting emails, and mimicking legal tone, it was enticing. This, too, would save time. Improve accuracy. Let you “focus on what matters.” And nearly three-quarters of lawyers say they plan to integrate it into their workflows (hai.stanford.edu).

But unlike past innovations, this one doesn’t parse rules. It predicts patterns. That difference matters, because what sounds like analysis is often just approximation. The result? Hallucinations. Confident, plausible nonsense. In AI terms, a “hallucination” is a fabricated claim presented as fact. In legal terms, it’s a misstep that could get you sanctioned.

A comprehensive study by Stanford’s RegLab and the Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence evaluated the performance of leading AI legal research tools, including those from LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters. The findings were sobering: these tools produced hallucinated responses in over 17% of queries (law.stanford.edu).

These errors aren’t merely academic; they can mislead practitioners, influence case strategies, and, if unchecked, erode trust in AI-assisted legal tools. And when lawyers present AI-generated content in court without verifying it, they don’t just risk embarrassment—they risk sanctions. As of mid-2025, at least 120 such incidents have been documented in U.S. courts (mashable.com). These cases involve attorneys submitting briefs with AI-generated, non-existent references, often without proper vetting, leading to judicial reprimands and financial penalties (washingtonpost.com).

One example: in Lacey v. State Farm General Insurance Co. (D. Cal. May 6, 2025), the court admonished counsel for submitting an AI-generated brief containing fabricated citations. The judge not only struck the filing but also ordered the attorneys to show cause why further sanctions shouldn’t be imposed. Another: in a 2025 case involving Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith LLP, the 14th-largest U.S. law firm, multiple attorneys were sanctioned after submitting court documents generated by ChatGPT that cited fictitious cases. The court imposed $31,000 in sanctions, citing the firm’s failure to supervise the use of generative AI and to perform basic citation checks (reason.com).

As Stanford Law’s experts recently argued, we’re entering a transitional moment—where courts, lawyers, and technologists must collectively define where liability for these hallucinations lies and how to manage it (law.stanford.edu). These cases join a growing list of warnings from the bench that generative AI is not an excuse for professional negligence.

Why AI bungles legal analysis

AI doesn’t think. It predicts. And in the legal world, prediction without comprehension is a dangerous game. Law isn’t just a set of rules; it’s a system built on precedent, interpretation, and context. A model that doesn’t truly understand the difference between dicta and holding—or even which jurisdiction it’s referencing—can’t produce reliable legal analysis.

One key issue is language. Legal documents are dense, intentionally nuanced, and packed with jargon that even seasoned practitioners sometimes debate. LLMs trained on general data often misread that nuance or gloss over it entirely. Even when you bolt on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to provide source documents, the system can still cherry-pick, misunderstand, or misrepresent those sources. The Stanford research showed this clearly: even AI tools from top legal publishers hallucinated in 17% to 33% of tested prompts.

And the data they rely on? Often incomplete. Many legal databases are proprietary. Models trained without access to full case law, regulatory texts, or up-to-date opinions are left guessing—and they guess with confidence.

In other industries, a hallucination might be a typo. In law, it’s a breach of duty.

Who’s responsible when AI gets it wrong?

You don’t need to be a practicing attorney to understand what’s at stake. When AI tools start generating legal content—drafting motions, summarizing cases, predicting outcomes—those outputs carry weight. Whether you’re in a firm or a marketing seat, the ethical implications are real.

The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct place the burden of competence on practitioners, but competence doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s supported—or undermined—by the systems and tools professionals rely on. If a model can’t distinguish between a binding decision and a law review article, should we really be feeding it into our workflows unchecked?

And as more judges issue standing orders around AI disclosures, this becomes not just an ethical matter but a procedural one. Transparency isn’t optional. Practitioners must vet AI outputs with the same diligence they apply to any human colleague’s work.

So where does that leave us? Not in a rejectionist stance, but in a more measured one. Adopt the tech, but pair it with protocols. Audit the tools, train your team, and understand what your models are doing. In short: treat AI like the intern it is—talented, fast, but not ready to fly solo.

AI is your intern, not your partner

So, what does responsible AI adoption actually look like in a legal context?

It starts with transparency—about what your tools can do and, more importantly, what they can’t. If a platform won’t tell you how it was trained or what it uses for citations, it hasn’t earned your trust.

It continues with oversight. Treat every AI-generated document like it was written by your most promising—but greenest—first-year associate. Verify every case. Follow every citation.

And finally, it requires education. Not just CLEs, but operational training. If your firm uses AI, everyone—from partners to paralegals—should know the basics of how it works, where it fails, and how to catch those failures before they go out the door.

This isn’t about slowing down innovation. It’s about making sure the tools we trust with legal analysis don’t undercut the systems they’re meant to support.

Yes, generative AI has real upside. It can speed up document review, spot patterns, and even improve client communications. With the right infrastructure—strong retrieval systems, curated datasets, human oversight—it becomes a powerful complement to the legal workflow.

But let’s not pretend it’s ready for everything. Drafting appellate briefs from scratch? Not yet. Parsing jurisdictional nuance in 50-state surveys? Hard pass. The core issue isn’t a lack of horsepower—it’s that these models don’t understandthe law. They predict what text looks like, not what it means.

So while there’s a lot of noise in the legal space right now about sanctions and slip-ups, the smarter conversation is about boundaries. Use AI where it helps. Know where it falls short. And never outsource your professional judgment to a tool that can’t tell the difference between a precedent and a prediction.